Amid the peace of Mount Hope Cemetery in Mattapan, there’s one section that stands out. Playwright Christina Chan sits in the middle of this neglected area and thinks about the first generation of Chinese immigrants in the United States.

“The rest of the cemetery is beautiful,” said Chan, sitting amid overgrown grass and toppled headstones. “But this broken section is where the first Chinese men who came came to Boston are buried.”

“I don’t know who they are,” Chan said. “I see their names on their grave sites and the year they died.” The Chinese Historical Society of New England has identified 1,500 Chinese immigrants who found their resting place at Mount Hope, the earliest record of interred date is 1930s.

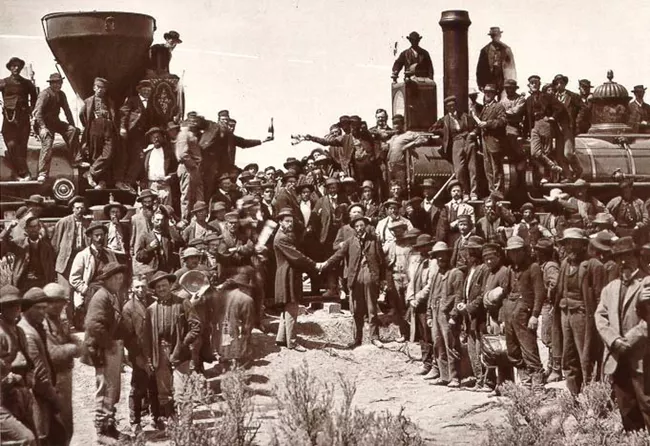

In the 1800s, suffering a drought in southern China and lured by tales of gold, villagers sent young men to California. Many found gold mines already depleted and faced sabotage from established miners. As the U.S. began railroad construction, immigrants from around the world were recruited. The Chinese proved particularly adept at this work. However, despite comprising 80% of the railroad workforce, there are no Chinese faces in the commemorative photo at Utah’s "Golden Spike" ceremony celebrating the completion of the coast-to-coast line.

Chan’s play, “The Fortune Teller,” seeks to explore the roots of this discrimination and suffering, drawing inspiration from the Chinese cultural affinity for superstition and gambling, evident during New Year celebrations, card games, and mahjong sessions. Yet, beyond that, Chan’s play is an opportunity to put Asian voices rarely heard on stages in Boston front and center. That has deep meaning for Chan, but also for the directors, actors and audiences for her work.

“I thought about the men that were toiling away on the railroad, toiling away in the mines, that when men who were lynched, who were forced to move from these Chinatown’s that were burned down by angry mobs of, of white men were banned from having their wives join them in the U.S.” Chan said. “The Chinese Exclusion Act [of 1882] was unique in that it targeted a particular race based on your skin color.”

“I want to bring my voice about injustice on that [racial injustice] as a playwright,” Chan said. “This is my medium to do that.”

“Chinese people don’t believe in health services,” Chan said, explaining why she chose to write about a fortune teller in the 1800s. “They go to the fortune tellers as an alternative to mental health services.” This perspective informs the narrative and themes explored in the play, making it a compelling exploration of the Chinese immigrant experience in America, rooted in culture and history. “I’m bringing it from the 1800s to now,” Chan said.

Chan describes her play, co-produced by CHUANG Stage and TC Squared Center in Boston from Oct. 28 to Nov. 4, as a “scaffold,” where all the creatives to pile on their ideas, thoughts and talents through the production. She says the process helps her become a better writer.

In 2018, Alison Yueming Qu was a theater student at Emerson College. She remembers sitting in the audition room for an especially important show. “It was an annual big performance that everybody wanted to get in,” said Qu. “There was a racially ambiguous role, so every single student of color was called to that audition.”

She remembers thinking, “Every single person of color that I know in the department is here.” She realized that “the opportunity was so limited that every single person of color was just like, ‘I don’t care what it is, I just need a role.’” Qu and two other theater students noticed the predominantly white narrative in the college’s theater productions, despite a significant creative Asian population.

“What they teach and what they made in Emerson was really, really white.” Qu said.

Qu sees the same lack of diversity in Boston’s theater scene “It has been far too long that this has become the norm in Boston. We aren't here just to be a tokenized portion of your season. We envision a theater scenario propelled forward by Asian artists and audiences,” she said. That realization spurred her to start CHUANG Stage, a translingual theater company.

“I wanted to make a theater company, where our season excites every single Asian American in the city,” Qu said.

The new theater’s reach soon extended beyond the school’s confines. A surge in interest showed that not only Emerson students but also a broader Boston population craved a theater experience tailored to the Asian American community.

As CHUANG Stage evolved, it fostered numerous collaborations, partnering with various theater companies and organizations. But despite its growth and expanding influence, its founder was intent on preserving its roots at Emerson. “When we started out, we were student organization,” Qu said. “It still stay at Emerson.” Qu said she wanted that birth place remain for the next generation, CHUANG Lab is now a sister organization with CHUANG Stage.

“The Fortune Teller” traces a family’s story from China in the 1800s to the present day in America. Jade McCarthy (Jamie Lin), is an adoptee and an Asian American journalist working on a story about sex trafficking. She discovers that women and girls as young as 14 are being trafficked, and most of the victims are people of color. Despite being laid off without her story being published, she does not give up on her investigation and finds that her biological mother (Karla Goo Lang) was one of these victims. Together, they discover their ancestor, Lin Wong (Mordecai Choi), who was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Mattapan.

Lin Wong came to the United States in the 1800s as an herbalist for a crew of Chinese laborers. Before his departure from China, he was anxious and went to ask his Sifu (Cantonese for “teacher”), who was a fortune teller (Tony SooHoo) about his destiny.

Lin Wong finds work building the transcontinental railroad. To his surprise, the new herbalist on the crew turned out to be his Sifu. The two of them were also united in their anger about the injustices suffered by Chinese workers. They parted ways after the Golden Spike Ceremony. Lin Wong invited his Sifu to run a herbal shop together, but Sifu declined.

Many years later, after Tacoma’s Chinatown burned down in a wave of anti-Chinese violence, Lin Wong’s Sifu visited Boston’s Chinatown, where he learned that there was an herb shop for sale. He bought the shop but lost it gambling to raise money to send to his wife and son.

This play connects the dots between heart-wrenching history and the reality of tough issues.

Chan hopes seeing themselves on stage will have an impact for audiences. It already has for the actors. “I’m no longer the only Asian in the room,” said Jamie Lin, who plays Jade McCarthy. “Our families all have various Chinese backgrounds so we can all bring in what we know.”

“I’ve always enjoyed being on stage,” Lin said. “But I don’t think I’ve actually played like an explicitly Asian character, until I actually was involved in an early reading of The Fortune Teller.”

In the past, Lin has played a lot of racially ambiguous roles. But in this one, she could feel that a Chinese character had an experience she was familiar with. The final scene of the play takes place in a graveyard. “We go through the ceremony for what we would do for Qingming Festival tomb sweeping,” Lin said, “Which is something I used to do a lot with my family.”

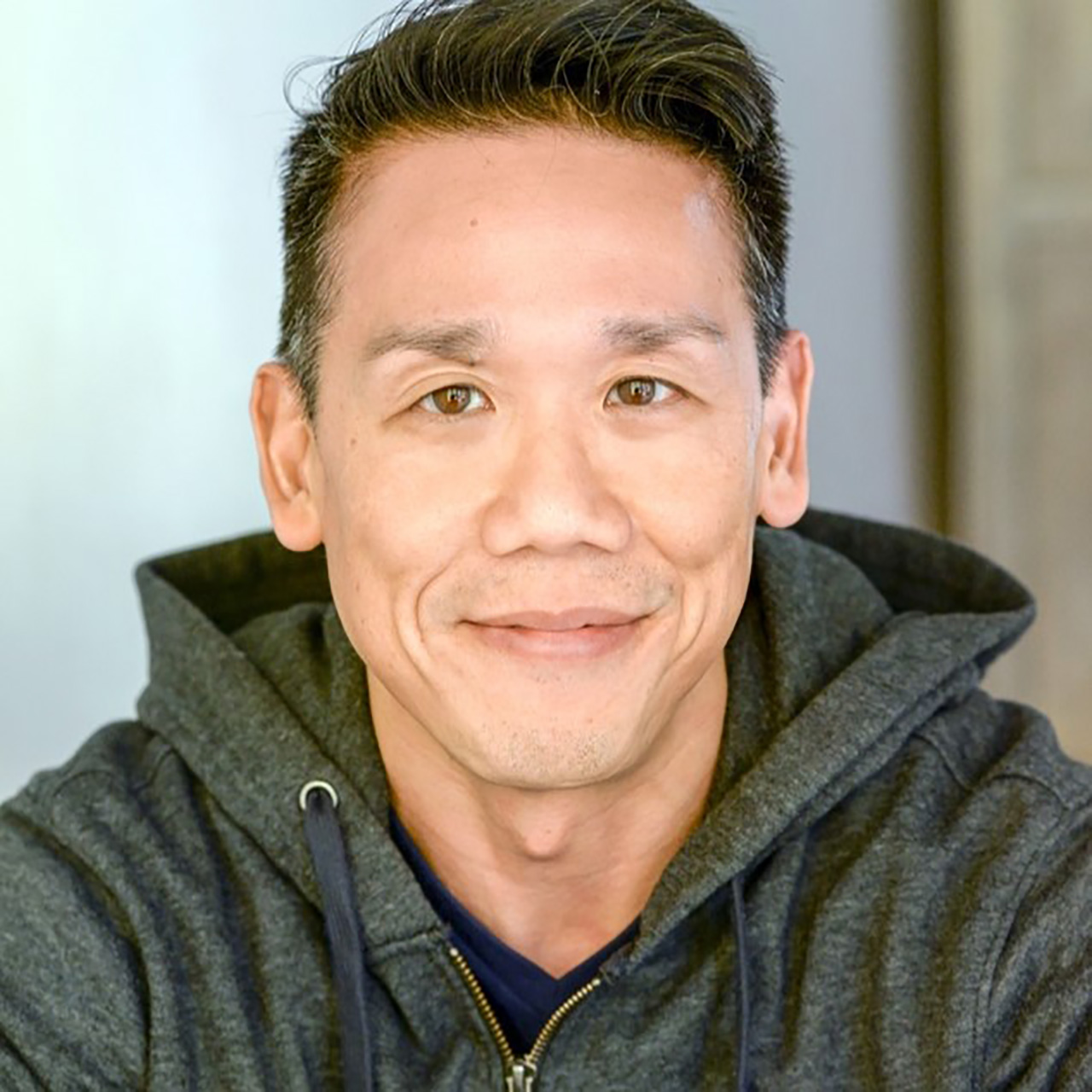

Tony SooHoo plays the Fortune Teller in the play. Other than his acting experience in theater, he also acts in different types of productions, such as television, commercial, etc.

SooHoo said this experience with the group is “amazing.” “There were so many Asians or Asian Americans that you know,” SooHoo said. “I think it’s a little more comfortable working with them.”

“We’ve been performing are relevant to our upbringing,” SooHoo said. “Everyone in the cast has something similar in their background.”

“I stepped into this theater area for like the last few years only, so I’m not sure if how much more they’ve had since a few years ago,” SooHoo said, “but I have poked around on different casting sites for theaters from the place, and there don’t seem to be a lot of Asian stories.”

SooHoo is optimistic about the current generation of students. He sometimes does student plays at Emerson and Boston University. “A lot of them are not Asian American, maybe they are international students come here from China or someplace else to come study here,” SooHoo said. “But they’re they’re still interested.”

“I’m sure some of these students will look around and Massachusetts and they'll want to look for more roles and plays to do out here,” said SooHoo.

Qu says the theater still faces some difficulties. “Boston doesn’t have a lot of space to perform,” Qu said. “I wanted to continue to call for action for some contract sector, to continue to invest in what we do and what everybody else is doing.”

“Budget is annual and you want to make sure that it grows, you never want to come back down,” Qu said, The most important thing is to make sure they can have enough budget to keep doing their works. “Because coming back down means your number comes back down, and it means that either you have to cut a show or you have to let people leave.”

“I’ve been thinking that how do I get into the community?” Qu said. “Like how do I make sure that people feel like this is for them?”

The opening night of the play on Oct. 28 was sold out. “People are genuinely excited about us,” Qu said. Unlike when the theater started, “No one is like, ‘Who are they?’” A full house is only part of the equation for Qu. “Selling out is a indicator of success, but I’m curious to go in there and see what kind of conversation we’re having.”

Min Li was an ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher in Boston’s Chinatown for decades. Seeing the play on the second night reminded her of her own journey. “When we first moved to America, I was in Chinatown in New York,” Li said. She moved to America just before the Cultural Revolution. She was 15 and it took her family eight years to come to the America, due to the Exclusion Acts and the National Origins quota system in the Immigration Act.

“I was physically assaulted a lot,” Li said. “This ‘Chink, chink, chink’... I was only 15 years old. I was so innocent. I didn't speak English.”

She said the play reflects the history of the Chinese community. “History is racist. We can deal with it, but it’s still here, still tearing the country apart, ” Li said. She’s made a difficult effort to assimilate into the local community.

During the pandemic, “Anti-Asian hate crime rose up to such an extent, that I didn't walk outside after sunset” Li said. “It’s almost like a mission to promote and preserve this history more than ever in order to combat the Anti-Asian [voices]," Li said.

Katya Zykina and Alex Akerblom are actors for television. Before seeing the play, they did not know the history of Chinese railroad labor. “I had no idea about this part of history before, but now I will be aware of it,” Zykina said.

As an actor, Zykina is familiar with barriers to immigrants. “I get auditions,” she said, “but I don’t get booked because of my accent.”

“I don’t think anyone should be give less chance or opportunity for any reason,” Akerblom said.

Jiekai Gu is an international student from China who has been in the U.S. for eight years. Before seeing the play, she had not learned about the history of Chinese Americans.

“Yes, nowadays Asian Americans still suffer some hidden discrimination...or you can see some verbal violence online as well, and I see hate crimes in the news,” Gu said. “I rarely realized this before. All sectors of society nowadays try to bridge the inequality between races, but early immigrants really contributed a lot.”

“When you go to movie theater... and realize the top show of the month is ‘Everything Everywhere All At Once,’ or ‘Turning Red,’ it makes you think about yourself as a smaller kid walking into a movie theater, and then the first thing that you see is ‘Mulan.’ The impact of someone being able to see themselves reflected in mass culture is really powerful. What I’m working on right now is to ensure that the city sees us.”

“Girls were being sold off or being sent as sex slaves here to the U.S. to service these men that were already here in the 1800s. That’s still happening in poor Asian countries. As a playwright, this is my medium to bring my voice to speak about injustice... Hopefully that will make other people curious about our history. And as Asian American women, we can look at ourselves and say, ‘Wow, I see.’ It’s not in the U.S. history textbooks. Not everybody knows about the 1882 Exclusion Act.”

“It makes it possible for people to go out see [Asians in leading roles]. And then they believe that they can actually do it. So if there’s any Asian actors out there just shy about going out there... maybe this will entice them to go out and do it. The more awards that they start winning, the more people will realize that there really are Asian films out there... showing Asian American stories. It doesn’t always have to do with fighting martial arts.”

“I’m always gonna say no, there’s not enough representation... I had to think, ‘Could a theater produce this work? Like do they even have a number of Asian actors available to play parts?...’ We produce a festival of short plays every year called PlayFest and that is a great way to get a lot of AAPI writers together and actors on stage. That’s actually how I met a lot of people in recent years. So we're trying but there can always be more... The way Asians are treated in America today has its roots in history. There are a lot of similar parallel experiences.... You can see a foundation laid that we're still grappling with today.”

According to a June 2023 report on grants given by the Mass Cultural Council (MCC), 7.7% of the individual grantees were self-reported as Asian or Asian American in their profile, slightly more than the percentage of the state population, suggesting efforts by MCC to encourage arts groups in communities of color.

This year, CHUANG Stage got $5,850 as Cultural Sector Recovery Grants for Organizations from MCC. The grant was offered to Massachusetts cultural organizations, collectives, and businesses negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If there’s more little theater in the neighborhood in the area and it’s promoted well, I think there’ll be more people inclined to go,” Soohoo said. “I feel like more in the community will come out.”

“I think there could always be more [Asian American theaters], but I’ve been happy to see how it’s growing,” said Lin.

“I think the change is coming because the next generation is rising,” Qu said.

Qu feels that there’s still a long way to go, but she’s optimistic. “We need more public space for the arts in Boston, we need more funding for people to be able to provide these job opportunities to Asian American artists. And then we can present these stories on stage where people feel see and then we also reflect the experience of what everybody else is doing out there,” Qu said. “There’s a lot of artists here in Boston that deserve to go upward, upward, and upward.”

“The more I do this work, the more I feel like that I’m not alone,” Qu said.

“Fortune can change,” said Soohoo as the fortune teller in the play. “Destiny remains constant.”

Produced by candidates for the MS degree in the Media Innovation & Data Communication program at the Northeastern University School of Journalism. © 2023