In 2016, Yashica Dutt was a 29-year-old graduate student at Columbia’s School of Journalism, writing on arts and theater and strolling through the streets of New York. To even Dutt’s closest friends, her life looked fulfilling and full of promise. That changed when she learned of the death of a PhD student in India, his suicide letter, and its gut-wrenching contents: “My birth is my fatal accident.”

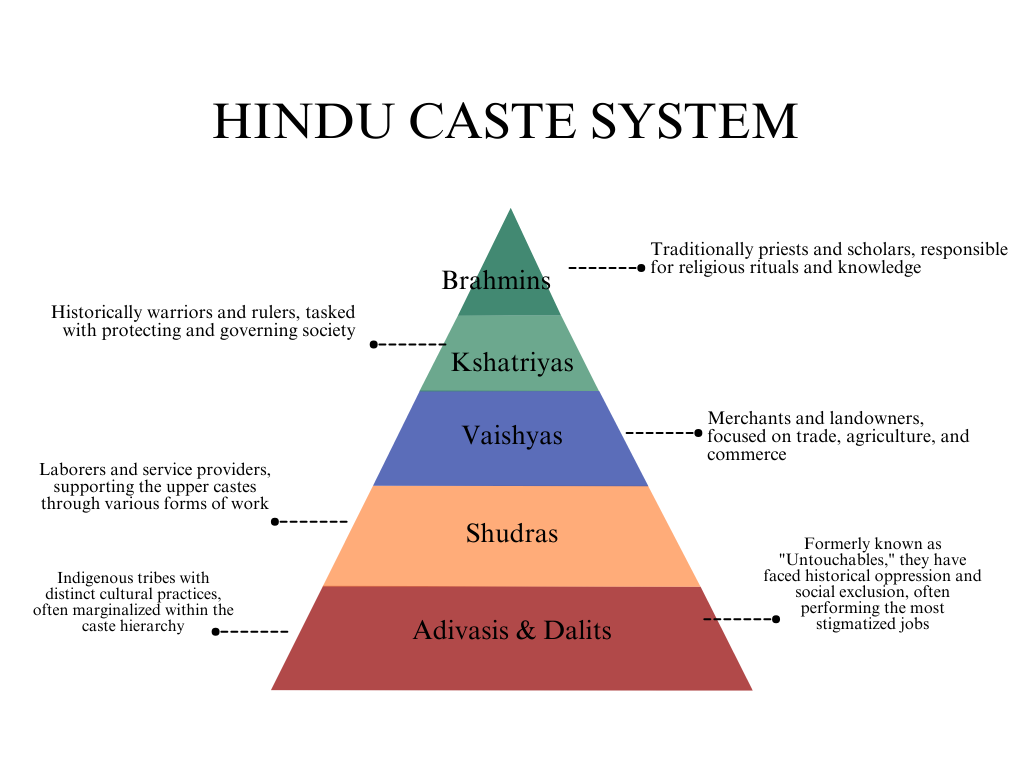

Dutt had never met Rohith Vemula, but they shared an identity: both were Dalits, members of the lowest rung of India’s rigid caste system. Vemula’s suicide followed punitive actions taken by his university in response to his activism for Dalit rights.

Dutt made a decision to reveal a part of herself she’d long ignored and kept secret. “I did not want people to know that I came from a manual scavenging caste,” said Dutt, who had “passed” — a phenomenon not dissimilar to racial passing — as upper caste for most of her life.

Dutt had good reasons to hide her Dalit identity. Restricted from education or gainful employment, for centuries Dalits engaged in manual scavenging, the gruesome task of cleaning and removing human waste from sewers and open drains by hand, often without any protective gear. The most recent Indian census in 2011 identified 1.3 million manual scavengers, over 90 percent of them women. Though banned in 1950, following India’s independence from British rule, the caste system’s 3000-year-old legacy continues to penetrate deeply into Indian society; its repercussions still felt today.

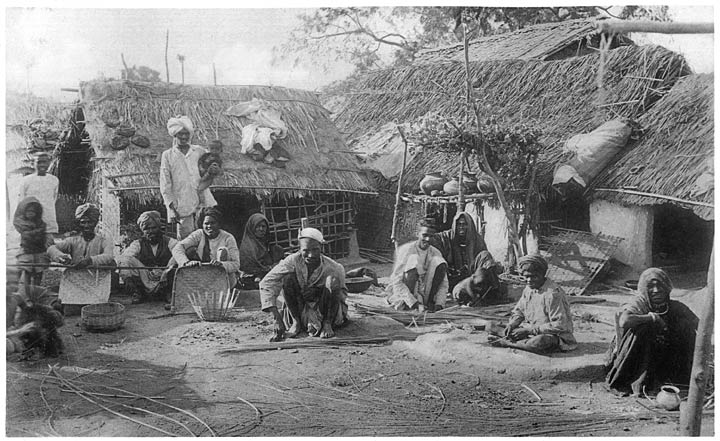

Basors (a Dalit caste) making baskets of bamboo in 1916. Image from "The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume II" by R.V. Russell.

Trapped at the intersection of caste, class, and gender, Dalit women have systematically had their agency stripped away, leaving them with limited opportunities for education and employment. Despite affirmative action policies, layered forms of patriarchy are deeply entrenched in Indian society, severely hindering Dalit women’s access to opportunities.

When they do gain access, they face systemic discrimination, including casteism from superiors and peers, violence from both “Savarna” or upper-caste men and Dalit men, and oppression from Savarna women. Dalit girls and women are regular victims of the most heinous acts of sexual violence, often used as a tool to reinforce caste superiority, with little recourse in the judicial system. Only 2% of the reported rape cases against Dalit women end in conviction.

A Dalit woman in Bombay, India, in 1942

As B.R. Ambedkar, a prominent Dalit scholar and principal architect of the Indian Constitution, put it, “To be a Dalit woman is to be the Dalit of the Dalits.” Shailaja Paik, a scholar at the University of Cincinnati, expanded on that, writing that a Dalit woman is the “slave of the slave.”

Marked by resilience in the face of overwhelming odds, Dutt, along with a handful of Dalit women today, is finding success, navigating spaces where their identities once limited their aspirations.

“When you have to fight to get access to books, to literacy, to information, it becomes all the more precious and more prized for you. Because it’s not just you… you’re not just gaining knowledge and ideas. It’s also a way for you to break out of this cycle of poverty that you have been a part of,” said Dutt.

India’s reservations program — the world’s largest affirmative action initiative — sets aside quotas for Dalits and marginalized castes in government roles and educational institutions. These serve as a vital lifeline for Dalit women, enabling access to education, employment, and representation. They are also a highly contentious topic in upper-caste society, which views the system as unnecessary and unfair, often directing their resentment toward those who benefit from it.

Nivedita Narender, an assistant professor of sociology at Delhi University whose research focused on the experiences of high-achieving Dalit women, recalls one of her subjects saying, “I’m always referred to as the person who came through quota. So much so that anything that I do is never considered meritorious.”

“When you hide a part of who you are, it comes with a great deal of shame. And that shame leads to the feeling that you are never going to be good enough.” Yashica Dutt

“I became the breadwinner of my family, so at every step, I kept fighting because I had this agency through studies and a good academic record,” said Divya, a first-generation scholar pursuing her doctoral studies in gender and caste at the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology in Indore who asked that her real name not be used. She recalls how her parents, who dropped out of school very early in the small South Indian village where they grew up, took pride in her achievements despite not understanding what “publishing a paper even means.”

“They have a general assumption that we are dumb. We don’t know much about anything. We just came for the sake of coming,” said Divya, who experienced ostracization from friends and mockery from her mentors after they found out about her Dalit identity.

“I cried for so long. I wanted to go home. I used to feel like I was very low and not equal to the people here, and I did not have much knowledge,” said Divya.

Dalit women persevere despite numerous obstacles, driven by a determination to prove their doubters wrong and uplift their communities and fellow women. This desire to pay back the community is ubiquitous among most accomplished Dalits.

“This is the sad reality. We have to live through it, and we have to challenge it,” said Divya, acknowledging that while it may not be able to achieve revolutionary change, “You can do whatever is possible in your everyday life.”

Divya’s lived experiences have driven her to work at the challenging intersection of caste, class, and gender. Immersed in the pursuit of caste and gender justice and often speaking out in the face of resistance, she embodies the motto: educate, agitate, and organize.

Dalits are not exempt from their identity’s unyielding clutch, even when far removed from India. The pervasive impact of the caste system is evident in the United States’ South Asian diaspora, particularly in Silicon Valley.

“I had managers from Indian backgrounds who would pull me down if they knew my caste,” said Maya Kamble, a software engineer in Washington, D.C., and president of the Ambedkarite Association of North America (AANA), an anti-caste organization in the U.S.

Kamble recalls an instance where a manager dismissed a casteist remark he made, calling her "ill-fated," as a joke upon confrontation. As a woman in tech, her experiences underscore the dual discrimination faced by Dalit women. "I don’t think my manager would have done this to a man," Kamble said. "He did it because I am a woman."

Concealing her real name, Kamble operates publicly under an alias as she continues to advocate for the Dalit cause. “For me, making a difference through regulations and systemic changes is more impactful,” Kamble said.

Seattle became the first city to ban caste discrimination in the U.S., a bill she ardently supported. A similar measure in California, which would have made it the first state to ban caste discrimination, passed the legislature in October 2023 but was vetoed by Governor Gavin Newsom.

“I don’t think my manager would have done this to a man. He did it because I am a woman.” — Maya Kamble

Kamble’s advocacy efforts, Divya’s dedication to a career exploring caste and gender, and Dutt’s influential voice, all highlight the resilience exhibited by Dalit women and their passion for giving back to their community.

“I broke all those barriers,” said Dutt. “But there are people who have not been able to break them. It is my job to talk about what it is like to be a woman and how our lives are shaped by caste, by gender.” Her voice rises, “That is what drives me today, to build a community of other Dalit people who break new barriers.”